“Knowledge is power, information is liberating. Education is the premise of progress, in every society, in every family” – Kofi Annan.

I am, by all accounts, extremely lucky. I grew up in a comfortable house in Sydney with two tertiary-educated parents. I went to a private school. My Mum drove me every morning until I was old enough to drive myself. At some point in my final year I decided I wanted to study international relations and law at university and so I did. I took these things for granted, even while my parents told me over and over again how incredibly privileged I was to have an education.

I was 11 when 9/11, the ‘Tampa’ and ‘Children Overboard’ happened, each within a few months of each other. If was the first time I remember consciously noting the politics that underpinned a conversation about refugees and asylum seekers. Everybody seemed to weigh in. An old woman at the bank told my Fiji-Indian father to ‘get back on his boat’. My Year Six teacher showed our class a 60 Minutes segment about asylum seekers and explained that they were coming to take our parent’s jobs. The practical distinction between ‘refugee’ and ‘asylum seeker’ became blurred. Legal definitions were ignored.

Matthews talks of an Australia where “the figure of the ‘refugee’ serves to establish an exclusionary Australian national identity which differentiates, recentres and reconstructs ‘us’ over and against ‘them’”[1]. I grew up in the shadow of this ‘us’ and ‘them’ mentality amongst wealthier immigrants who had come to Australia ‘the right way’ and people born in Australia who felt somehow superior, while conveniently ignoring Indigenous claims to the land.

My parents made no attempt to hide their distaste for governments who used the plight of refugees and asylum seekers as a political football. My mother is an academic who has taught tertiary learning skills for more than 30 years. She recalls Deng, a former child soldier, working all night and then turning up to an academic writing workshop she was running. Deng now owns a law firm in Western Sydney. When I was younger, stories like this, of the resilience of the human spirit, resonated with me

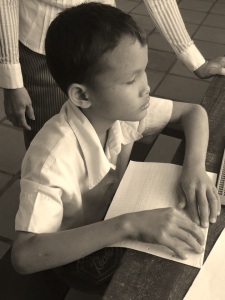

As soon as I was old enough, I started travelling. I saw firsthand the struggle for quality education in countries crippled by systemic poverty, war and conflict. In Cambodia, some children are forced out of school by their parents to beg on the streets. In Colombia, with its high rate of teen pregnancy, particularly in impoverished areas, many girls have no option but to leave school to care for their children.

I have also met refugees awaiting resettlement. Some have been educated in their country of origin and desperately want the same for their children. Some are illiterate in their native language and formal education remains a distant dream. One thing has consistently stood out in our conversations: the opportunity for themselves or their children to receive an education in their country of resettlement is a priority.

Needless to say, my perspective on education has changed significantly. As hard as I worked academically, I was undoubtedly given a huge head start. I was lucky to not have to fight for my right to an education as a girl. I was lucky that the six-minute commute between my home and my school didn’t cost me my life. I was lucky to have the resources I needed to do my homework – a computer, parents who could help, my own bedroom with a desk and a chair. This was my foundation.

Foundations are invaluable, but do not come easily when one has been forcibly uprooted from their country of origin. Refugees undoubtedly face a myriad of obstacles during resettlement, and building a solid foundation from which they can truly benefit from formal education is near impossible without assistance.

This assistance is not as forthcoming as it should be. As of 2019, education policy and practice in Australia remains largely uninformed by the experiences of refugees in the Australian school system[2]. My sister is a primary school teacher with a Graduate Certificate in Teaching English to Speakers of Other Languages (TESOL) who prefers to work in schools with significant refugee populations. Her experience as an advocate for education equality amongst primary aged refugees in the Australian education system is fairly harrowing. It is underpinned by the frustration of having to send refugee students home to clearly traumatised parents who do not speak English and who cannot assist with homework or assignments. Inevitably, the same students return discouraged to the classroom the next day.

It is clear that the digital age has furthered an already significant divide between students of refugee backgrounds and those without. In many Sydney primary schools, a portion of the curriculum is taught online. Each student, sometimes from Year Four up, has a Google Account and content, including homework and assignments, are uploaded online. Students without access to a device or the internet are often directed to the local library which presents new problems: parents working two jobs each cannot always drive their children, a basic level of computer literacy is required. For newly arrived students of refugee backgrounds, who have never used a computer before, who are not confident speaking English, and whose parents cannot assist, this can be a monumental and overwhelming task.

This was the experience of one of my sister’s students, a Tamil refugee whose family had been detained on Christmas Island before being settled in Australia. The student recalled his life on Christmas Island with the familiar innocence of a child – there were ‘pools’ – in reality, dug-out holes that had filled with water. Still, he suffered from residual trauma that impacted his ability to retain information. On top of this, while other students worked from laptops or tablets that they could take home with them, the student and approximately five others, the majority from refugee backgrounds, took it in turns to work from the single classroom desktop. It was inevitable that he would fall behind. The support that my sister could offer as a single teacher in a classroom of 30 students was limited.

This article is in no way intended to be a generalisation and nor does it assume that every refugee’s experience is the same. There are children, even adults, of non-refugee backgrounds who face similar difficulties. There are refugees who arrive with foundations already in place. It does acknowledge, however, that refugees are a particularly vulnerable group in society because their very classification denotes displacement, often accompanied by trauma and war. Despite this, their experiences, resilience and skills have the potential to greatly enrich Australia if given the right tools.

We can only reap what we sow as a society. If we don’t encourage and support equal access to education for all Australians, we will lose out. If we don’t actively invest in bridging the digital divide, refugees will continue to be disenfranchised when it comes to the right to education. If we don’t assist with building foundations, individuals within vulnerable groups will miss the opportunity to realise their potential and pursue meaningful futures.

Sowing the seeds for a better educational experience for resettled refugees cannot be done in isolation. The rhetoric surrounding refugees and asylum seekers in Australian discourse has long been underpinned by xenophobia. This paradigm needs to shift. We need to understand the very real plight of refugees and the level of human suffering that occurs during forcible displacement. The key to bringing about change is for enough people to acknowledge deficiencies in society and desire better for the future.